- Homepage

- Author

- Aleister Crowley (6)

- Arthur Von Mayer (15)

- Bram Stoker (8)

- Charles Dickens (9)

- Dan Brown (7)

- Dr. Seuss (18)

- Ernest Hemingway (9)

- Frank Herbert (9)

- George Orwell (12)

- Howe, George (6)

- J.k. Rowling (44)

- J.r.r. Tolkien (16)

- Kurban Said (6)

- L. Frank Baum (9)

- Margaret Mitchell (8)

- Mark Twain (8)

- Robert Paul Smith (6)

- Rudyard Kipling (16)

- Stephen King (28)

- Wendell Berry (9)

- Other (2640)

- Binding

- Brand

- Bandai (6)

- Bratz (16)

- Coomodel (5)

- Dc Collectibles (3)

- Disney (3)

- Fire Toys (2)

- Hasbro (6)

- Hot Toys (15)

- Kenner (5)

- Mattel (7)

- Mcfarlane Toys (3)

- Mezco (3)

- Neca (3)

- No Brand (23)

- Pokemon Game (2)

- Random House (4)

- Super Duck (3)

- Tiger Electronics (2)

- Vintage Bookworms (3)

- Wizards Of The Coast (13)

- Other (2762)

- Language

- Publisher

- Alfred A. Knopf (31)

- Bloomsbury (22)

- Doubleday (32)

- Dutton (9)

- Easton Press (19)

- Franklin Library (11)

- G.p. Putnam's Sons (9)

- Grosset & Dunlap (11)

- Harcourt Brace (11)

- Harper & Brothers (20)

- Harper & Row (16)

- Jonathan Cape (12)

- Macmillan (22)

- Marvel Comics (10)

- Random House (54)

- Scholastic Press (9)

- Steiger (15)

- The Viking Press (9)

- Viking (8)

- Viking Press (17)

- Other (2542)

- Year Printed

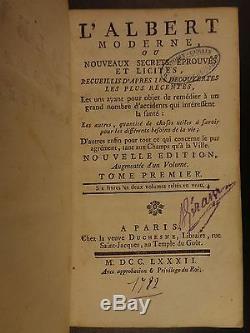

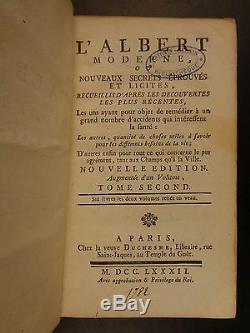

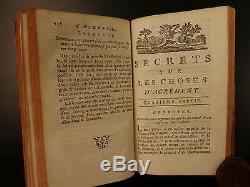

1782 Albertus Magnus SECRETS Herbal CURES Magic Potions Occult Sciences Alchemy

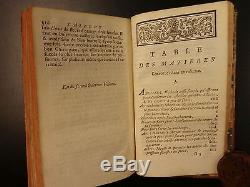

1782 Albertus Magnus SECRETS Herbal CURES Magic Potions Occult Sciences Alchemy. + Pleasures of Chocolate & Many New Secrets. 1200 1280, also known as Albert the Great and Albert of Cologne, is a Catholic saint. He was a German Dominican friar and a Catholic bishop. He was known during his lifetime as doctor universalis and doctor expertus and, late in his life, the term magnus was appended to his name.

He is often referred to as the greatest German philosopher and theologian of the Middle Ages. This edition book has several new secrets that were not included in earlier editions of this book.

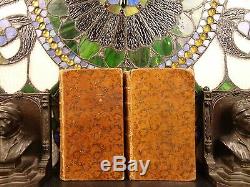

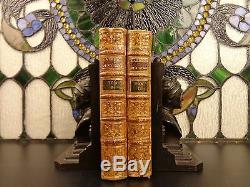

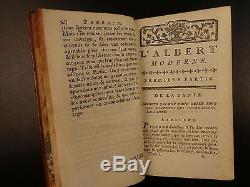

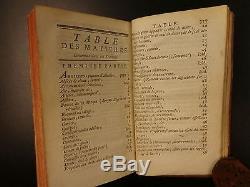

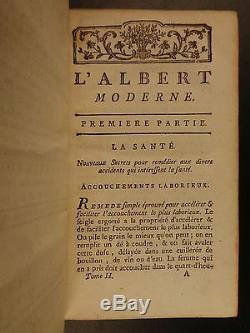

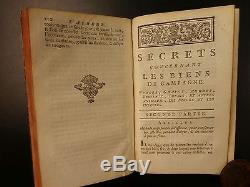

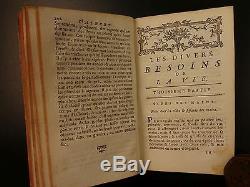

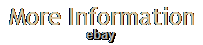

Secrets include remedies of multiple health issues, life pleasures such as chocolate, maintaining silverware, how to keep eggs fresh, the secret of crossing a river without knowing how to swim, plus much more! Pons Augustin Alletz; Albertus Magnus. L'Albert moderne; ou, Nouveaux secrets éprouvés et licites, recueillis d'apres les découvertes les plus récentes, les uns ayant pour objet de remédier à un grand nombre d'accidens qui intéressent la santé: les autres... Utiles à savoir pour les différens besoins de la vie.. Paris, La Veuve Duchesne, 1782.Wear as seen in photos. Tight and secure leather binding. Complete with all xii + 372 + 343 pages; plus indexes, prefaces, and such.

6.5in X 4in (16.5cm x 10cm). (before 1200 November 15, 1280), also known as Albert the Great and Albert of Cologne, is a Catholic saint. [1] Scholars such as James A. Söder have referred to him as the greatest German philosopher and theologian of the Middle Ages. [2] The Catholic Church honours him as a Doctor of the Church, one of only 36 so honoured. It seems likely that Albert was born sometime before 1200, given well-attested evidence that he was aged over 80 on his death in 1280; more than one source says that Albert was 87 on his death, which has led 1193 to be commonly given as the date of Albert's birth. [3] Albert was probably born in Lauingen (now in Bavaria), since he called himself'Albert of Lauingen', but this might simply be a family name. Most probably his family was of ministerial class; his familiar connection with (being son of the count) Bollstädt noble family was a 15th century misinterpretation what is now completely disproved. Albert was probably educated principally at the University of Padua, where he received instruction in Aristotle's writings. A late account by Rudolph de Novamagia refers to Albertus' encounter with the Blessed Virgin Mary, who convinced him to enter Holy Orders. In 1223 (or 1229)[4] he became a member of the Dominican Order, and studied theology at Bologna and elsewhere.Selected to fill the position of lecturer at Cologne, Germany, where the Dominicans had a house, he taught for several years there, and at Regensburg, Freiburg, Strasbourg, and Hildesheim. During his first tenure as lecturer at Cologne, Albert wrote his Summa de bono after discussion with Philip the Chancellor concerning the transcendental properties of being. [5] In 1245, Albert became master of theology under Gueric of Saint-Quentin, the first German Dominican to achieve this distinction. Following this turn of events, Albert was able to teach theology at the University of Paris as a full-time professor, holding the seat of the Chair of Theology at the College of St.

[5][6] During this time Thomas Aquinas began to study under Albertus. Bust of Albertus Magnus by Vincenzo Onofri, c. Albert was the first to comment on virtually all of the writings of Aristotle, thus making them accessible to wider academic debate.The study of Aristotle brought him to study and comment on the teachings of Muslim academics, notably Avicenna and Averroes, and this would bring him into the heart of academic debate. During his tenure he publicly defended the Dominicans against attacks by the secular and regular faculty of the University of Paris, commented on St. John, and answered what he perceived as errors of the Islamic philosopher Averroes. In 1259 Albert took part in the General Chapter of the Dominicans at Valenciennes together with Thomas Aquinas, masters Bonushomo Britto, [8] Florentius, [9] and Peter (later Pope Innocent V) establishing a ratio studiorum or program of studies for the Dominicans[10] that featured the study of philosophy as an innovation for those not sufficiently trained to study theology. This innovation initiated the tradition of Dominican scholastic philosophy put into practice, for example, in 1265 at the Order's studium provinciale at the convent of Santa Sabina in Rome, out of which would develop the Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas, the "Angelicum"[11].

In 1260 Pope Alexander IV made him bishop of Regensburg, an office from which he resigned after three years. This earned him the affectionate sobriquet "boots the bishop" from his parishioners. [12] After this, he was especially known for acting as a mediator between conflicting parties. In Cologne he is not only known for being the founder of Germany's oldest university there, but also for "the big verdict" (der Große Schied) of 1258, which brought an end to the conflict between the citizens of Cologne and the archbishop. Among the last of his labors was the defense of the orthodoxy of his former pupil, Thomas Aquinas, whose death in 1274 grieved Albert (the story that he travelled to Paris in person to defend the teachings of Aquinas can not be confirmed). Roman sarcophagus containing the relics of Albertus Magnus in the crypt of St. Andrew's Church, Cologne, Germany. After suffering a collapse of health in 1278, he died on November 15, 1280, in the Dominican convent in Cologne, Germany.Since November 15, 1954, his relics are in a Roman sarcophagus in the crypt of the Dominican St. [13] Although his body was discovered to be incorrupt at the first exhumation three years after his death, at the exhumation in 1483 only a skeleton remained. Albert was beatified in 1622. He was canonized and proclaimed a Doctor of the Church on December 16, 1931, by Pope Pius XI[12] and the patron saint of natural scientists in 1941.

Albert's feast day is November 15. Albertus Magnus monument at the University of Cologne. Fiesolano 67, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana.

Albert's writings collected in 1899 went to thirty-eight volumes. These displayed his prolific habits and encyclopedic knowledge of topics such as logic, theology, botany, geography, astronomy, astrology, mineralogy, alchemy, zoology, physiology, phrenology, justice, law, friendship, and love. He digested, interpreted, and systematized the whole of Aristotle's works, gleaned from the Latin translations and notes of the Arabian commentators, in accordance with Church doctrine. Most modern knowledge of Aristotle was preserved and presented by Albert. His principal theological works are a commentary in three volumes on the Books of the Sentences of Peter Lombard (Magister Sententiarum), and the Summa Theologiae in two volumes. The latter is in substance a more didactic repetition of the former. Albert's activity, however, was more philosophical than theological (see Scholasticism). The philosophical works, occupying the first six and the last of the 21 volumes, are generally divided according to the Aristotelian scheme of the sciences, and consist of interpretations and condensations of Aristotle's relative works, with supplementary discussions upon contemporary topics, and occasional divergences from the opinions of the master. Albert believed that Aristotle's approach to natural philosophy did not pose any obstacle to the development of a Christian philosophical view of the natural order. Albert's knowledge of physical science was considerable and for the age remarkably accurate. His industry in every department was great, and though we find in his system many gaps which are characteristic of scholastic philosophy, his protracted study of Aristotle gave him a great power of systematic thought and exposition.An exception to this general tendency is his Latin treatise "De falconibus" (later inserted in the larger work, De Animalibus, as book 23, chapter 40), in which he displays impressive actual knowledge of a the differences between the birds of prey and the other kinds of birds; b the different kinds of falcons; c the way of preparing them for the hunt; and d the cures for sick and wounded falcons. [15] His scholarly legacy justifies his contemporaries' bestowing upon him the honourable surname Doctor Universalis. In De Mineralibus Albert claims, The aim of natural philosophy (science) is not to simply to accept the statements of others, but to investigate the causes that are at work in nature. Aristotelianism greatly influences Albert's view on nature and philosophy.

[7] Another example of his reason to formally search for the causes is in his treatises on plants, he begins with the principle, experiment is the only safe guide in such investigations. His studies of Aristotle and theology show their colors in nearly all of his works and volumes.Albert placed emphasis on experiment as well as investigation, but he respected authority and tradition so much that many of his investigations or experiments were unpublished. Albert would often keep silent about many issues such as astronomy, physics and such because he felt that his theories were too advanced for the time in which he was living. Albertus Magnus, Chimistes Celebres, Liebig's Extract of Meat Company Trading Card, 1929. In the centuries since his death, many stories arose about Albert as an alchemist and magician. Much of the modern confusion results from the fact that later works, particularly the alchemical work known as the Secreta Alberti or the Experimenta Alberti, were falsely attributed to Albertus by their authors to increase the prestige of the text through association.

[16] On the subject of alchemy and chemistry, many treatises relating to alchemy have been attributed to him, though in his authentic writings he had little to say on the subject, and then mostly through commentary on Aristotle. For example, in his commentary, De mineralibus, he refers to the power of stones, but does not elaborate on what these powers might be. [17] A wide range of Pseudo-Albertine works dealing with alchemy exist, though, showing the belief developed in the generations following Albert's death that he had mastered alchemy, one of the fundamental sciences of the Middle Ages. These include Metals and Materials; the Secrets of Chemistry; the Origin of Metals; the Origins of Compounds, and a Concordance which is a collection of Observations on the philosopher's stone; and other alchemy-chemistry topics, collected under the name of Theatrum Chemicum. [18] He is credited with the discovery of the element arsenic[19] and experimented with photosensitive chemicals, including silver nitrate. [20][21] He did believe that stones had occult properties, as he related in his work De mineralibus. However, there is scant evidence that he personally performed alchemical experiments. According to legend, Albert is said to have discovered the philosopher's stone and passed it to his pupil Thomas Aquinas, shortly before his death. Albert does not confirm he discovered the stone in his writings, but he did record that he witnessed the creation of gold by transmutation.[22] Given that Thomas Aquinas died six years before Albert's death, this legend as stated is unlikely. In his Little Book of Alchemy Albert said that alchemic gold and iron lack the properties of natural gold and iron, alchemical iron not being magnetic and alchemica. The item "1782 Albertus Magnus SECRETS Herbal CURES Magic Potions Occult Sciences Alchemy" is in sale since Friday, November 2, 2018. This item is in the category "Books\Antiquarian & Collectible". The seller is "schilb_antiquarian_books" and is located in Columbia, Missouri.

This item can be shipped worldwide.

- Binding: Leather

- Subject: Science & Medicine

- Topic: Occult

- Special Attributes: 1st Edition

- Origin: European

- Original/Reproduction: Original

- Year Printed: 1782

- Printing Year: 1782